Commerating The Hoggs Hollow Mine Disaster at York Mills Subway.

“Breaking Ground,” a commemorative quilt by Laurie Swim hanging at York Mills subway station. Photo by Rémi Carreiro/Torontoist.

This week saw the installation of a quilt at York Mills subway station to honour five men who lost their lives in what became known as the Hogg’s Hollow Disaster. The deaths of Pasqualle Allegrezza, Giovanni Correglio, Giovanni Fusillo, Alessandro Mantella, and Guido Mantella while working on a watermain under the Don River on March 17, 1960, and the press coverage of the exploitation of their fellow Italian immigrant construction workers led to the strengthening of Ontario’s labour laws.

Work conditions for the thousands of Italian immigrants who laboured during Toronto’s postwar suburban boom were anything but ideal. While union-fought guarantees of lunch breaks and certain safety requirements eased the workday of those working on sites within the city of Toronto, workers on suburban projects faced conditions that included lack of proper sanitation, poor safety inspections, illegal withholding of vacation pay, unpaid overtime, cheques that often bounced, and groundless threats of deportation. The fear of going without work and being unable to support their families in Canada and Italy forced the workers to tolerate the exploitation of their labour. Toothless provincial regulations, some drafted during the Edwardian era, offered little protection. The “sandhogs” who worked in underground tunnels faced constant dangers from cave-ins, exposure to gas leaks, electric shocks, small fires, and maladies related to air decompression, like the bends.

It was only a matter of time before tragedy occurred.

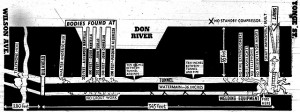

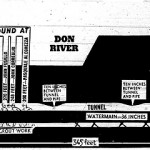

The Hogg’s Hollow watermain project was dogged by bad luck. The new line was intended to connect a pumping station on Wilson Avenue in Armour Heights with the water distribution network at York Mills Road and Victoria Park Avenue. The project was scheduled for completion during the summer of 1959, but the original contractor ran into financial difficulties. Guarantee Co. of North America took over the contract in July and appeared to be committed to expediency more than safety. Foremen concerned with the lack of proper safety precautions were ignored or fired. Former workers later testified that the tunnels lacked fire extinguishers and resuscitators, the timber supports weren’t strong enough, grout was not used on the floor of the tunnel to keep out sand and silt, and there were no extra air compressors. Despite these problems, the site was deemed to meet existing safety standards.

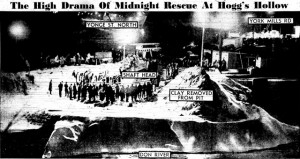

Around 6 p.m. on March 17, a dozen workers were underground in a compression chamber west of Yonge Street, welding steel plating. The welding was supposed to have stopped several hours earlier, but the site boss overruled the concerns of superintendent Murray Frank. It was believed that an electric wire that fed the torches overheated and caught fire. Two foremen noticed smoke drifting into the main shaft. Half of the workers escaped through a tunnel to the east and emerged on York Mills Road. They headed to the main shaft to release a valve that would allow the smoke to blow out of the tunnel, but found it was stuck. North York firefighters soon arrived and were instructed to wait at least thirty minutes before watering the tunnel in the hope the blaze would extinguish itself—otherwise the tight tunnel would collapse once water hit it. The air compressor was left on to clear the smoke.

The six men still in the tunnel found themselves trapped by rising temperatures, toxic smoke, and rising levels of sand, silt, and water. Frank and foreman George Sandor attempted to go down and thought they heard at least three voices moaning. Sandor later told the Globe and Mailthat he “wanted to go farther but the heat was terrific. I could feel my lungs as though they were going to burst. God only knows I tried, but I couldn’t make it. I had to come out.”

Among the trapped, Belgian Walter Andruschuk tried to keep the others calm:

I tore my shirt off, soaked it in water and covered my face with it. The other five did that but kept their heads up. They started screaming “Mama Mia.” They got down on their knees and started to pray. I couldn’t keep them quiet. I told them to stay put, that the boys upstairs would come down and get us out. They wouldn’t keep their heads down and conserve energy. The smoke was awful and then the water hit us. It came up to our knees. I was scared but I knew they would come and get us out. But the heat was draining our energy. There was a glimmer of hope; I could see a light from the shaft and I just knew we would be all right. I started back toward the shaft. The other five wouldn’t come with me. They were screaming and down on their knees praying. I grabbed Pasquale Allegrezza by the shirt and started dragging him along the pipe. There was no room to carry him and I couldn’t fight the smoke any longer. I had to let go of Pasquale. Another few feet and I had to put my face down on the pipe. I was sleepy. And then I guess I passed out. Just before I passed out I was afraid for the first time that I would not get out.

Confusion reigned on the surface, as various emergency agencies, civic officials, priests offering last rites, and bystanders gathered at the site. The lack of onsite backup safety equipment only fuelled the lack of coordinated effort among all (the following day, a civil defence rescue expert told the Telegram that “people were phoning all over the place for equipment they knew nothing about”). Several workers volunteered to go down to find the trapped men, including foreman Jack Corigliano:

When they told me a bunch of the fellows were trapped at the other end, I felt sick. But I said I would help try and get them out. They told me I would have to wait. I guess it was too hot for anybody in there at first. After an hour, maybe two, the boss asked me if I still wanted to go in and look for the others. I said I’d go. It was hotter than hell down there. The going was rough. I had to crawl on my hands and knees. There wasn’t much room to move—sand, water everywhere. And smoke. It took me about five minutes to reach them. By that time my eyes were running from the smoke. My head was dizzy. It kept turning around and around. Then I could see them lying there. They were dead. I could tell they were dead. I could feel it. I tried to lift one. I don’t know who. But there wasn’t enough room to get a grip and pull him. If there were two of use, we could have done it. But I was all alone on that side of the pipe. It was no use, the smoke was killing me. I had to get back. When I got out I told the boss that they were in there. He started to cry. I begged him to let me go back in—but he sent me to the hospital.

Meanwhile, Andruschuk had continued to crawl slowly westward toward an exit shaft. Around 9 p.m., rescuers pulled the delirious sandhog to the surface and sent him to hospital. Hope for the others faded when Allegrezza’s corpse, which took half-an-hour to move three hundred feet, was brought up around 2 a.m. Relatives who had come to the site screamed. The other bodies were found over the next day, with recovery hampered by the unbearable heat and shifting silt. The Mantella brothers were found huddled together, while efforts to free Correglio took six hours.

Within a few days a “Tunnel Tragedy Fund” was set up to benefit the families of the victims on both sides of the Atlantic. Metro Toronto Chairman Frederick Gardiner initiated the fund with a one-hundred-dollar donation. Through events such as an April benefit concert at Massey Hall organized by Johnny Lombardi, the fund raised thirty-five thousand dollars by October. An anonymous contractor also offered Correglio’s widow and children an apartment rent-free for a year.

A week after the disaster, a requiem mass was held at St. Agnes Roman Catholic Church for Fusillo and the Mantella brothers. Among the attendees was Telegram reporter Frank Drea, who had followed the story from the start. In Canadese: A Portrait of the Italian Canadians, Kenneth Bagnell noted that Drea had been tracking the construction industry for some time:

Drea was in the prime of his career as a reporter with a special interest in labour matters. He had contacts with the unions, the companies, the government, at every level, and his stories were often dramatic, written not in the cold language of economics, but in moving prose, about human suffering. He was the son of an Irishman, and while not a socialist, his underlying sympathy and passion were with the rank and file, with immigrant tradesmen like his father. Over his desk on the fourth floor of the Telegram building on Bay Street, he argued passionately with editors over union issues, declaring time after time that tradesmen and labourers, so many of them Italian, were mistreated in Toronto as a matter of course—from the unsafety of their working conditions, to the integrity of their paycheques.

An editor approached Drea to write a front-page story about the issues facing Italian labourers, which the editor figured would keep the story in the public eye. After the headline on the March 25 edition of the paper screamed “SLAVE IMMIGRANTS,” Drea and the editor were called into publisher John Bassett’s office. Expecting Bassett to be angry (as developers were among the Telegram’s advertisers), the publisher uttered one word: “tremendous.” Bassett then told his audience about how his father had told him stories of the awful conditions Italian immigrants worked under in Montreal at the turn of the century and how he was shocked that similar practices still existed in Metro Toronto. He told Drea that he could write as much as he wanted—“I want you in the paper every day with it…I want this covered from start to finish. I want to see the Telegram lead in putting a stop to it.

For the next two weeks the front page of the Telegram was filled with accounts of workers being ripped off and forced to endure unsafe worksite conditions. Among those reading Drea’s articles was Ontario Premier Leslie Frost, who sensed action needed to be taken as soon as possible to both bring the province’s labour laws out of the Dark Ages and to build support among the Italian community for the Progressive Conservatives, who had often been viewed suspiciously. His labour minister, Charles Daley, had claimed immediately after the tragedy that provincial regulations had been followed and made other statements that fuelled the rage of Italians and the Telegram. After the coroner’s inquest determined that callous management, incompetent foremen, inexperienced workers, a disorganized rescue, and inefficiency at the Department of Labour caused the disaster, Frost ordered a Royal Commission to look into construction safety and exploitation of immigrants. Though no criminal charges were ultimately laid, the sacrifice of the five men at Hogg’s Hollow brought about improvements in the conditions that had led to their demise.

Additional material from Canadese: A Portrait of the Italian Canadians by Kenneth Bagnell (Toronto: Macmillan, 1989), Such Hardworking People: Italian Immigrants in Postwar Toronto by Franca Iacovetta (Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1992), and the following newspapers: the March 18, 1960, and March 19, 1960, editions of the Globe and Mail; the March 18, 1960, March 19, 1960, March 22, 1960, March 24, 1960, March 25, 1960, April 4, 1960, and April 8, 1960, editions of the Telegram; and the March 18, 1960, edition of the Toronto Star.

Article by By Jamie Bradburn, Torontoist.

First Response Comments:

We hear of these mine tragedy’s frequently. I can only imagine the horror of being buried alive and loosing hope of being rescued with every passing minute. Known as ‘Sandhogs’ back in the ’60’s, these jobs often fell to immigrant workers who had little option for work. They endured at best, extremely poor conditions just to be able to provide for their families and even then, often that was not a guarantee. One hopes that things have changed in the 21 Century, but I sometimes wonder. Mining is a very dangerous job, and I suspect it takes a certain ‘type’ of person to be able to handle it and the stress and uncertainty that goes along with it. I always impress on my students that your safety is number one. If you don’t take care of yourself, no one else will as they are too busy taking care of themselves. I you have ever worked underground or in similar circumstance, I would love to hear your comments in the box below…